|

Richard Nixon's Last Secret

Richard

Nixon took the secret to his grave. Thirty years after the Watergate

break-in, there's a ra ce to unerase - and it's hitting high gear.

By

Tom McNichol

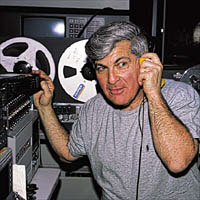

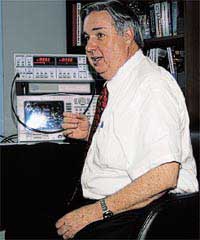

Paul

Ginsberg owns more than 100 tape recorders, most of them crammed into

his basement audio lab, a low-ceilinged lair in Spring Valley, New York,

that he likes to call the Tape Cave. There's a clunky Revox reel-to-reel

from the early '70s that looks like it's straight out of the Partridge

Family's garage; 13 Tascam cassette decks modified to copy tapes at

various speeds; dozens of microcassette recorders scattered about like

matchbooks; and a Nagra SNS, the subminiature reel-to-reel that went

up in smoke at the beginning of every episode of Mission: Impossible.

But it's another reel-to-reel that holds a special place in Ginsberg's

collection. "This is the baby," he says, watching the tape revolve.

"It's a Sony TC-800B, the same kind used by the Nixon White House to

record the Watergate tapes."

As

it happens, Ginsberg has dusted off his old Sony just in time, because

the Nixon White House is suddenly hotter than ever. Capitalizing on

the 30th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, former Nixon counselor

John Dean has stirred up a media frenzy with a book that claims to unmask

the case-breaking source Deep Throat. Meanwhile, Ginsberg is among a

handful of forensic audio experts vying to crack the infamous 181é2-minute

gap in a White House tape recorded three days after the burglary.

Photo

by Martin Esseveld

"If

I manage to do it," says forensic audio guru Ginsberg, "my basement

will become a national historic spot." |

The gap appears in a recording made on June 20, 1972, as Nixon discussed

the Watergate break-in for the first time with his chief of staff, H.

R. Haldeman. When the White House revealed that part of the conversation

had been "accidentally" erased, a majority of Americans came to believe

that the man who insisted "I am not a crook" was that and more. Nixon

resigned in disgrace in 1974, but in the years since Watergate, the gap

has remained a tantalizing mystery.

Watergate

scholars can't help but wonder: What could be incriminating enough to

make this the only Nixon tape erased, when so many hours of blatant

cover-ups, dirty tricks, expletives, and Jew-baiting were left untouched?

"It's the big unknown," says David Coleman, assistant professor at the

Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, who's

studying Nixon's taped conversations for the university's Presidential

Recordings Project. "It could contain something innocuous. Or it could

be another smoking gun."

Tape

342, as it's known by archivists, was last tested in 1974 by a panel

of audio experts, who concluded that the erasures were done in separate

segments. Whoever erased the tape pressed Record, stopped the tape,

and hit Record again, between five and nine times - hardly an accidental

erasure. But the panel was unable to retrieve any of the lost conversation.

"The experts concluded that it was a deliberate erasure," emails Bob

Woodward, who along with colleague Carl Bernstein did much of the groundbreaking

reporting on Watergate for The Washington Post. "The public got

the message: The tapes had very damaging information. The exact content

of the 18 1/2-minute gap would be interesting."

Photo

by Martin Esseveld

Inside

Ginsberg's Tape Cave: multispeed reel and cassette recorders, signal

processing units, parametric equalizers, a dynamic noise eliminator,

bandpass filters, and much more. |

Last summer, the National Archives and Records Administration decided

it was time to take another look, in the hope that advances in digital

technology would be able to restore the conversation. NARA invited audio

experts to demonstrate how they might retrieve intelligible speech. The

competition - a battle of the bands among a dozen or fewer audio experts

- is expected to last more than a year. Before any of them get their hands

on the original tape, they must show they can retrieve sound from test

erasures without doing damage. Those who succeed will get a crack at the

real thing.

The

recovery effort promises to be as tricky as Nixon himself. It's like

solving a Zen riddle: What is the sound of no one talking? And NARA

isn't paying any of the audio experts, though the attention they'll

draw may be its own reward. Ginsberg is well aware of the prestige that

would come with a successful decoding of Tape 342. "If I do manage to

do it," he says, punching Stop on the TC-800B, "I guess my basement

will become a national historic spot."

An

inveterate tinkerer who counts Thomas Edison as one of his heroes, the

56-year-old Ginsberg has built or modified much of the equipment in

the Tape Cave. Since 1974, he has run a business called Professional

Audio Laboratories out of his home. Most of his work involves enhancing

and authenticating surveillance tapes and other audiovisual evidence

presented in criminal and civil proceedings. He's been involved in more

than 1,600 court cases, including the Waco trial. He enhanced surveillance

tapes recorded inside the Branch Davidian compound to show that the

fire was set from within - not by the surrounding government troops.

For

the Nixon case, Ginsberg is hoping that his TC-800B will give him a

leg up on his competition. By carefully measuring the class characteristics

of the Sony - wow and flutter (the percentage of low- and high-frequency

speed fluctuations), head alignment, and track configuration - Ginsberg

hopes to establish a technical baseline against which to compare subsequent

testing. Being a lifelong audio packrat just might pay off. "This is

one of those times," he says, "when it helps to have a crazy old piece

of equipment."

Stroll into the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and ask

to check out Tape 342, and the archivists will look at you as if you've

asked to wipe your feet on the Declaration of Independence. Tape 342

is treated like a priceless heirloom, locked in a vault kept at precisely

65 degrees Fahrenheit and 40 percent relative humidity. The tape has

been played just half a dozen times in the last three decades, and only

then to make copies.

Qualified

researchers do have access to a copy. "I've listened to this thing more

times than I care to admit," says Michael Hamilton, supervisory audiovisual

specialist for the archives' Nixon Presidential Materials staff. "I've

listened to it very close and very loud. I can't detect any conversation.

But I haven't played with it electronically."

The

gap occurs during a conversation between Nixon and Haldeman three days

after the burglary of Democratic National Committee headquarters. Just

before the erasure, there's the distinct ticking of a clock in the background

- marking out the seconds of a doomed presidency. The overall sound

quality is terrible, even by the crappy technical standards of the Watergate

tapes. The tiny lavalier microphones hidden throughout the Oval Office

and Executive Office Building to record conversations were cheap and

poorly placed. The recordings were made on thin 0.5-mm tape running

at the unusual speed of 15é16 inch per second - half the speed

of a cassette recorder. The slow tape speed degrades the recording's

already poor signal-to-noise ratio. At the point of the first erasure,

the muffled conversation is suddenly replaced by a buzzing noise, presumably

the sound of a 60-cycle hum leaking from the power grid as interpreted

by a high-gain microphone input circuit. Throughout the gap, the buzz

occasionally drops in volume, but never is there any discernible speech.

When

the public learned in 1973 that the tape had been tampered with, Nixon's

personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods, stepped forward with a convoluted

story about how she could have been responsible. Woods said she was

transcribing the tape when she took a phone call and left her foot on

a pedal that may have caused the erasure. A widely circulated photo

of Woods re-creating her improbable lean across her desk led many to

believe that she was stretching more than just her torso. But even Woods

insisted that she was responsible for no more than five minutes of the

erasure.

The

fact that the tape contained as many as nine separate erasures contradicts

any notion that it was caused by an accidental press of the Record button.

The culprit was either very anxious to protect the president or was

a mechanical klutz. Both descriptions, Watergate scholars have noted,

fit Richard Nixon. The 37th president was laughably inept when it came

to technology. Haldeman recounts in his now out-of-print book, The

Ends of Power, that Nixon struggled with the most basic functions

of cassette recorders. The Army Signal Corps supplied Nixon with the

simplest recorder available so that the president could dictate memos

in the evening. But even then, the various buttons had to be marked

so Nixon could use the machine without mixing things up. Put a man like

that in front of a reel-to-reel, and it's easy to see how a simple erasure

could turn into a clumsy mess.

More

puzzling is why Nixon chose to erase this segment and no other. One

theory is that he sat down sometime in 1973 with the intention of erasing

all incriminating tapes, so that the Watergate special prosecutor couldn't

get his hands on them. Nixon began with Tape 342, the first recorded

conversation after the break-in, but quickly became overwhelmed. There

were more than 2,800 hours of tapes, and the way he handled a recorder,

it would have taken him a lifetime to erase everything. So the June

20 conversation was erased simply because it was the first Watergate

tape chronologically.

An

opposing theory is that the lost conversation is the one Nixon couldn't

bear anyone to hear. Even Haldeman's somewhat sanitized version supports

this. As he reconstructs it in The Ends of Power, a worried Nixon

spends part of the meeting setting the Watergate cover-up in motion.

During the discussion, Nixon is particularly concerned that the trail

will lead to White House special counsel Chuck Colson. Linking Colson

to the break-in would tie the burglary to the White House. "I know one

thing," Haldeman recalls Nixon saying. "I can't stand an FBI investigation

of Colson."

"Inadequate

as [Haldeman's] version might be, it fits with the overall evidence

in the case," notes Bob Woodward. "There was an effort to cover up and

conceal."

But

what Nixon said may pale in significance to the way he said it. Perhaps

there's a fragment of conversation, even an aside, that's so outrageous

that Nixon had to get rid of it. It could be something more incriminating

than the so-called smoking gun conversation held three days later, in

which Nixon instructs Haldeman to tell FBI investigators, "Don't go

any further into this case, period." Or a comment more thuggish than

telling John Dean that it wouldn't be a problem coming up with hush

money for the Watergate burglars: "You could get a million dollars.

And you could get it in cash." Something even more vile than Nixon ordering

Haldeman, "Bob, please get me the names of the Jews, you know, the big

Jewish contributors of the Democrats. All right. Could we please investigate

some of the cocksuckers?"

Audiotape consists of a thin plastic base coated with ferric oxide,

made up of microscopic magnetic particles. As the tape passes over the

record head, the ferric oxide particles are reoriented by the magnetic

field from the head. After recording, the tape is covered with patches

of magnetization of various depths and directions, which are translated

into sound. When a tape is erased, the erase head scatters the particles.

"It's not a kitchen floor, where if you strip away all the tiles, you

can see the original floor," says Ginsberg. "It's more like ripping

up all the tiles and randomly rearranging them."

Although

Tape 342 was recorded on a Sony TC-800B, it was erased on a Uher 5000

reel-to-reel. If the Uher performed a perfect erasure, the contest to

retrieve the lost conversation is over before it begins. But any number

of factors - a crack in the erase head, a dust mote on the tape or heads,

slack in the tape at startup, head misalignment - can result in only

a partial erasure. The fact that Tape 342 was recorded on one machine

and erased on another increases the chances of an incomplete erasure.

A decade ago, this wouldn't have mattered. But today's digital tools

can help make something out of what sounds like nothing.

Removing

unwanted sound with analog tools is akin to using a butter knife to

cut out a bruise in an apple. The knife may remove the bruise, but it'll

also carve out some of the good part. Digital audio tools are more like

a laser scalpel, allowing the user to make hundreds, even thousands

of fine cuts, shaving off specks of unwanted tones and noise so that

all that remains is speech. Ginsberg has put this technique to use already,

in a case that offers a glimpse at how he plans to attack Tape 342.

In

1997, a large New York brokerage house came to Ginsberg with a taped

conversation between two brokers, a crucial piece of evidence in a multimillion-dollar

lawsuit. The conversation was taped on a Dictaphone logging machine,

which records 60 channels across a 1-inch-wide tape - "a lot of tomatoes

to squeeze into one can," as Ginsberg puts it. The conversation in question

was on channel 19, but a malfunctioning amplifier rendered the speech

inaudible. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, Ginsberg contacted

Dictaphone and had them build a special tape head that played only channel

19. Then he modified the machine to run at four times normal speed,

further boosting the signal without increasing the noise. "At first

I didn't think there was a conversation there," recalls Ginsberg. "But

then I could hear a very, very, very faint muttering."

Next,

Ginsberg turned to an array of digital audio enhancement tools. He loaded

the audio onto the PCAP II - a sophisticated audio-filtering workstation

used by the FBI to clean up undercover surveillance tapes - which features

a toolbox of digital signal processors. There's a high-pass filter to

eliminate low-frequency "rumble," and a limiter for reducing gain on

sudden, loud input signals. Notch filters can be set to reduce the signal

level of an unwanted frequency. Comb filters attack harmonically structured

noises, such as the 60-cycle hum found on the Nixon tape. An inverse

comb filter enhances useful harmonically structured signals, such as

vowel sounds in speech, allowing the user to tease voices out of background

noise.

There's

also a tone remover that eliminates constant frequencies. Human speech,

which is highly intonated and constantly changing, is not affected.

Up to five onboard equalizers can be adjusted to boost frequencies in

the human voice range while filtering out extraneous noise. A 460-line

spectrum analyzer allows the user to see the audio being processed as

a waveform. An array of digital adaptive filters, like the PCAP, use

multiple microprocessors to continuously analyze the audio signal and

automatically make adjustments when they detect changes in the noise.

Moreover, they can operate in the speech frequency bandwidth to reduce

noise and not affect the voice.

After

running the brokerage tape through the PCAP, Ginsberg was able to recover

about 90 percent of the conversation, which helped exonerate his client.

"Even I was impressed," Ginsberg says. "This conversation came from

nowhere."

Of

course, success wasn't entirely in the tools. Whether through heredity

or training, Ginsberg is literally wired for sound, blessed with exceptional

hearing. His family is always complaining that volume on the TV is too

low, while he sits happily in his chair wondering what the fuss is about.

He drives a Lexus GS 300 for its acoustics - he says the car has a great

sound system and gives a quiet ride.

Photo

by Martin Esseveld

"If

we get a couple of words, we'll be ec static," says Reames, who

designed undercover recorders used worldwide. |

This will be Ginsberg's second brush with Tape 342. While he was employed

by Federal Scientific almost 30 years ago, a team of government officials

approached a division of the company with Tape 342 in hand, wanting to

retrieve speech from the gap. Ginsberg didn't work directly on the project,

but his company was responsible for the first of many failed attempts

to recover the 181é2 minutes. This time, Ginsberg wants to get

it right - but not for the political or historical implications. He can't

even remember if he voted for Nixon in 1972. "For me," he says, "it's

all about the technical challenge."

If

Paul Ginsberg is the Tinkerer, James Reames is the Spy. Reames, another

entrant in the Nixon Gap Challenge, worked for the FBI for 32 years,

at one point running the bureau's audiotape laboratory. He helped design

the Nagra JBR subminiature recorder, which for years was the standard

undercover recorder used by government agents worldwide. After leaving

the bureau, Reames started his own company, JBR Technology, which does

forensic audio work.

"I

know most of the experts who studied the 181é2-minute gap in

1974, and they are goooooooood," Reames says, in a soothing Southern

drawl that sounds like Andy Griffith extolling the virtues of a Ritz

cracker. "We'll have to get lucky to retrieve any of the conversation.

But this is one of those once-in-a-lifetime cases."

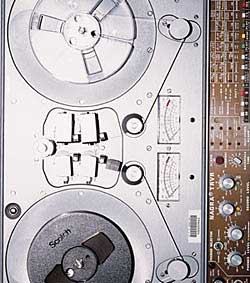

Like

Ginsberg, Reames has a Sony TC-800B. He plans to apply some of the same

techniques, with a few added twists. He'll play Tape 342 on a modified

Nagra reel-to-reel fitted with a small video camera and two high-resolution

mirrors mounted on either side of the tape path. A video record will

protect Reames if there's any question about damage. It could also reveal

oily smudges or even fingerprints. Reames could get lucky and find Nixon's

big, klutzy thumbprint. "We'd take any of his 10 fingers," he says,

smiling.

Photo

by Martin Esseveld

A

modified Nagara reel-to-reel, owned by audio expert James Reames:

Variable speeds allow searching for different sound frequencies,

while hi-res mirrors detect tape damage. |

He also plans to study the tape with magneto-resistive read/write heads,

used in computer hard drives. The heads can sense small changes in magnetic

direction, producing a detailed scan that can be used to map a digital

image of the sound. If there's enough of a bitstream, the digital images

can be translated into intelligible voices. Reames will use as many as

36 MR heads to scan the width of Tape 342, looking for a tiny "sliver

track" of recoverable speech.

To

find snatches of speech in the buzz and background noise, Reames has

made an array of filters that will look for speech tones. If he finds

signals that are aperiodic, it's a good indication that a word or a

sound may have occurred in that frequency. If Reames manages to extract,

say, the word yes, he can measure its frequency characteristics

and search for the same properties elsewhere. In this way, he may be

able to gradually piece together the message. "If we get a couple of

words, we'll be ecstatic," Reames says. "If we get 30 words, we'll be

even happier. And if we're lucky enough to recover the entire gap, we'll

probably have a heart attack."

Reames'

approach is being taken a step further by researchers working at two

of the Commerce Department's Boulder, Colorado, laboratories. Scientists

there have developed a technique known as second harmonic magneto-resistive

microscopy (SH-MRM) for forensic authentication analysis. It involves

passing a tape hundreds or thousands of times over a high-resolution

magneto-resistive head. The sensors in the head move back and forth

over the tape without touching it, gradually building up, line by line,

a topographic map of the tape's magnetic field at millions of points.

The mapped data can then be plugged into an imaging program. If enough

data is recovered, investigators can begin to rebuild the original signal.

The

SH-MRM technique is exacting; two inches of cassette tape can take an

hour to scan. "If you're passing a half-inch-wide tape over a 1-micron-wide

head," says David Pappas of the National Institute of Standards and

Technology, "you have to scan it about 12,000 times to realize the full

resolution."

One

way to speed up the scan is to construct a system with an array of sensors

- as many as 400 - to read many tracks simultaneously. Even with a single

sensor, SH-MRM has been able to recover sound from an otherwise unplayable

segment of tape rescued from a flight data recorder. The FBI is also

using SH-MRM to analyze the thousands of cassettes it receives each

year as evidence.

Pappas

considered applying SH-MRM to the Nixon tape gap, but after September

11, the NIST lab has been focused almost exclusively on homeland security

projects. "If somebody picks up our technology and applies it to the

Nixon tape, more power to them," says Pappas. "But right now we have

our hands full."

The

contest to retrieve the 18 1/2-minute gap promises to be a long-running

battle; at the National Archives, time tends to be measured in years,

not months. If one or more audio experts is able to recover sound from

the test tape without damaging it (and archivists are visibly nervous

about harming the original), they will be issued a standard request

for proposal. Once the bureaucratic formalities are satisfied, qualified

audio experts would get their hands on the original Tape 342, possibly

not until early next year.

Ginsberg

is already immersed in the test recording sent to him by NARA. It's

a fair approximation of Tape 342, a segment of speech and tones recorded

on a Sony TC-800B and erased on an Uher 5000. Ginsberg has started tinkering,

modifying his Dictaphone player to accept quarter-inch tape. After running

the tape through the system, Ginsberg identified six discrete channels

across the width of the tape that appear to contain signals - a good

start, but still a long way to go. "It's analogous to an astronomer

knowing where to point the telescope when he's looking for a celestial

body," Ginsberg says.

Ginsberg

is searching for a hidden world not in the infinite expanse of space,

but among the infinitesimal ferric oxide particles scattered across

a thin piece of plastic. Many hours of arduous investigation lie ahead,

and Tape 342 has so far guarded its secrets well. But it would only

be fitting if technology were responsible for revealing more about Richard

Nixon than he intended.

|